Ever since the Standard went up in 2009, the cards were in for the Gansevoort Meat Market.

Photo: Google Maps

We may soon see the last tailor ditch the Garment District and the last banker leave Wall Street. But the meat-packers might beat them. At least, per the plan announced today by the deputy mayor at a breakfast for real-estate power players — a plan that hinges on an agreement with the last tenants of a city-owned meat market on the north side of the Whitney Museum.

Maria Torres-Springer described a “cultural and artistic hub” that would rise there instead and add up to 600 apartments to a city in a housing crisis (with half of them marked as affordable) and up to 11,200 square feet of new public space, plus room for the Whitney to grow. The “hub” would replace a two-story brick building, put up in 1949, where the last seven wholesalers in the neighborhood lobbied to get space after some were sold and the Whitney took over another next door.

The museum’s agreement with the city then gave it the right to make the first offer on the site. It’s unclear how involved they were in this plan, but the museum’s president called it “a unique opportunity to expand.” The city press release describes the new public space as an “open pavilion” that could be operated by the High Line, which passes just to the east. But there’s no word yet on what the building could look like or how affordable those units might be — details that would be hashed out during the typical community-engagement process (which could get ugly. As one activist said, in response to the news, “Why is it not 100 percent affordable, if this is city property?”). The city also needs to persuade city planners to get rid of a restriction that limits the site to agriculture and was put in place when the Astor family donated the land.

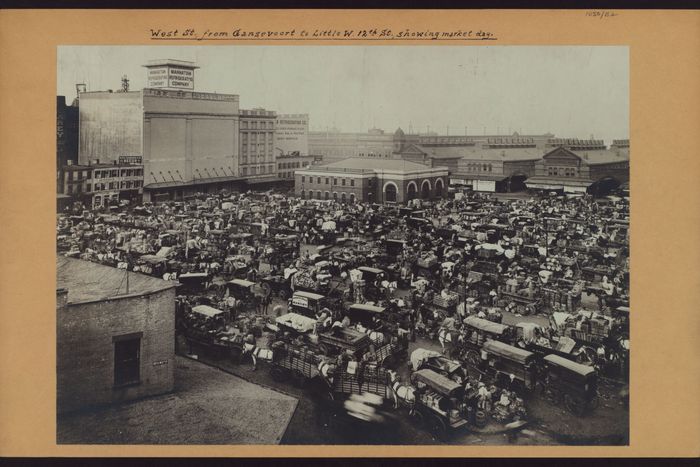

In 1900, the area was home to a vast open-air market that eventually developed the neighborhood into rows of shops and wholesalers, then started shrinking. The market the city is now rethinking was built in 1949 on the site of an old fort.

Photo: Courtesy NYPL

Locals have been quibbling for more than half a century about whether downtown’s meat markets are worth saving — the last of their kind or a traffic nightmare, a gritty feature or a health hazard. But when the Whitney opened, the trucks huffing in and out of loading docks next door seemed like part of the appeal with critics admiring how the building wedged itself into “the industrial grain” of a “blue-collar” neighborhood. By 2024, the market was not just the last of the neighborhood’s namesake industry, it was “the last remnant of that kind of real, gritty industrial manufacturing in the far West Village,” said Zack Winestine, a co-founder of the community group Save Gansevoort. “And I think it’s a tremendous loss. It kept things real.”

The mea- packers don’t seem to be fighting for their own preservation. Back in 2005, John Jobbagy, who owns the meat-packer J.T. Jobbagy, quelled rumors that the city was planning to level the co-op for housing. Today, representing the other tenants, he said in the press release that it no longer works for them and lacks “up-to-date standards for processing and distribution.” The owner of another tenant, London Meats, said the move wouldn’t hurt his business, which can now ship from anywhere. “I’ll be fine wherever I go,” said Michael Milano.

The current market serves as a shipping port with access off the West Side Highway.

Photo: Little Vignettes Photo/Shutterstock

The exodus is more annoying to the people further down the meat-packing food chain who have been driving to pick up from wholesalers here for a while — 120 years, in the case of Pino’s Prime Meats of Soho. “It affects small guys like me,” said owner Leo Cinquemani. “I’m going to have to travel further away to get stuff. I don’t know where I’m going to go.” But he couldn’t think of that on a Monday at lunch hour. “Sorry, I’m a little busy,” he said. And forgetting to hang up on a reporter, he shouted, “How much was that bacon?”